The Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute (IJC) recently had the pleasure of receiving a visit from Dr. Norma Gutiérrez at the Catalan Institute for Oncology/Germans Trias i Pujol Campus. Dr. Norma Gutiérrez is associate doctor in hematology at Salamanca hospital and lead researcher in the Multiple Myeloma Group at the Biomedical Research Institute of Salamanca (IBSAL).

Her main area of research is focused on understanding the genetic basis and pathogenesis of multiple myeloma and other monoclonal gammopathies using high-performance genomic technologies and functional trials. She also coordinates the cytogenetics studies of the Spanish Myeloma Group. She has published more than 140 original articles in international journals.

In her spare time Dr. Gutiérrez likes reading and walking.

Dr. Gutiérrez gave a paper at our campus entitled, Genomics in Multiple Myeloma.

We wanted to ask Dr. Gutiérrez to tell us more about the current challenges in multiple myeloma.

● Dr. Gutiérrez, what does it mean to be diagnosed with multiple myeloma?

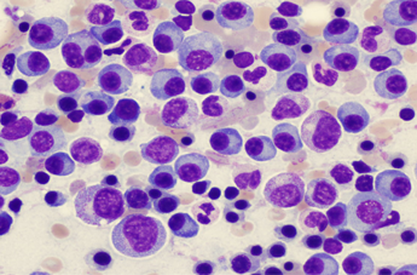

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematological cancer that affects plasma cells located mainly in the bone marrow. These cells are the ones that produce immunoglobulins or antibodies. In multiple myeloma the tumorous plasma cells produce large numbers of the same monoclonal antibody and these can be quantified in the blood and sometimes in the urine. The accumulation of tumorous plasma cells and the excessive production of monoclonal antibodies causes damage to various organs such as the bones and kidney leading to the symptoms that characterise this cancer.

Myeloma must be distinguished from a benign process called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), which occurs in approximately 1% of the general population and in 3% of healthy people over the age of 70. Although monoclonal antibodies and abnormal plasma cells are detected in MGUS, they do not cause any damage to the organism and consequently require no treatment. Nevertheless, it requires constant monitoring because with the passage of time there is a risk of it turning into myeloma.

● What treatments currently exist for patients diagnosed as having multiple myeloma?

Until recently treatment for multiple myeloma has been based on combinations of chemotherapy, which almost always includes melphalan and steroids. At the present time there are new drugs with mechanisms of action that are different from those of chemotherapy and these have improved response levels and prolonged patients’ lives. The most notable of these are the proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib and immunomodulatory drugs such as lenalidomide. The initial treatment is generally based on the combination of three drugs depending on the age of the patient given that with patients under the age of 65 high doses of chemotherapy are indicated followed by a transplant of hematopoietic progenitors.

● Over the last 10-15 years biological therapies have made great progress and have lengthened the periods in which multiple myeloma patients can be free of the disease. How do you think current therapies can be improved even more?

Exactly, there has been a significant increase in the number of options for treatment over the last 10 years. Such advances are key in a cancer such as myeloma, the natural course of which is characterised by successive relapses. There are a number of drugs, from new generations of proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory agents to monoclonal antibodies against the blood cells’ own antigens which enable relapses to be successfully treated and periods free of the disease lengthened.

But we are still far from using the therapeutic arsenal at our disposal appropriately. We have known for a long time that the evolution of patients with myeloma is very uneven, probably due to the fact that the biological characteristics of the cancerous plasma cells vary greatly from patient to patient. It can be assumed that the efficacy of drugs will be different depending on whether the cellular processes they modify are critical or not for a particular myeloma. So I think one way forward in rationalising the way drugs are currently used is to design trials, involving biological studies of cancerous plasma cells, that are far more ambitious than those we are accustomed to in order to determine what characteristics differentiate the myelomas that respond from those that do not.

● Your area of specialisation is focused on understanding the disease’s genetic basis. What do you think is the most important discovery made by your team with regard to the study of myeloma?

Given that the knowledge about the genomic basis of multiple myeloma that we have contributed is of modest proportions the most outstanding thing is probably to have observed, using advanced genomic techniques, that the clonal plasma cells of pre-malign entities such as monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance have the same genomic alterations as multiple myeloma. Why, from the genomic point of view, some apparently similar cells are capable of provoking multiple myeloma in some cases yet remain in an asymptomaticprocess in others is still an enigma in this pathology.

● How can the study of genetics help in improving current treatments for multiple myeloma?

It is true that therapeutic developments sometimes follow very different paths from those of advances in knowledge about the disease’s biology, specifically, genomic alterations. In fact, the mechanisms of action often become apparent much after having demonstrated the efficacy of the therapeutic agent. Having said that, it is undoubtedly true that the more we know about the genomic characteristics of the myeloma cell the more progress we can make in curing this disease.

Thanks to unstoppable technological development we have methodologies available that enable us to study the flow of genomic information from the DNA to the RNA virus and the protein using very small samples. This was unthinkable only a few years ago. We have the tools, now we only need to be audacious enough to know how to use them to get into the inner workings of the cancerous plasma cells while avoiding the risk of sailing on the surface of a sea of disconnected genomic data.

● The Josep Carreras Foundation has established a research centre specifically for leukaemia and other malignant blood diseases, the IJC. What do you think the repercussions of this will be in the field of science and for society in general?

Not nearly enough is invested in research. I believe that with a research centre devoted entirely to malignant blood diseases it is possible to optimise resources and focus them towards more exhaustive studies of the biology of these diseases. I also think it makes it easier for researchers working at different levels to concentrate their efforts on resolving more specific and better defined problems, thereby avoiding dispersion, at least in part. I have had the opportunity to get to know the Institute and I think that the projects underway are really attractive. In time this Institute could become an international beacon in the field of hematology.

The effects on society are more difficult to evaluate. When people are healthy, initiatives such as this often go unnoticed. But when these diseases knock at their door their commitment to research is much stronger. I think progress has been made in this too and that most people appreciate and support investment in cancer research because they know that one way or another it has an effect on their health.