Clinical trials

Clinical trials are medical studies involving healthy people or patients. These trials lead to new, safe and effective ways to prevent, detect or treat diseases.

The information provided on www.fcarreras.org is intended to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between patients/visitors to this website and their physician.

What is a clinical trial?

Clinical trials are a fundamental part of the medical research spectrum. Typically, the idea for a clinical trial usually comes from a laboratory. When researchers have evaluated a new treatment or procedure in the laboratory and using experimental animals, the most promising ones are considered for clinical trials. As studies go through a series of steps, called phases, researchers learn more about the treatment, its risks and its effectiveness.

Clinical trials are a fundamental part of the medical research spectrum. Typically, the idea for a clinical trial usually comes from a laboratory. When researchers have evaluated a new treatment or procedure in the laboratory and using experimental animals, the most promising ones are considered for clinical trials. As studies go through a series of steps, called phases, researchers learn more about the treatment, its risks and its effectiveness.

Each clinical trial has criteria describing who can participate: children and/or adults, patients or healthy volunteers, people with ethnic and racial backgrounds that make them more prone to certain diseases, etc. All clinical trials follow a carefully designed plan (or protocol) to protect health and answer specific research questions. The protocol describes what will be done to the persons included and what they can expect from the research team. It is important to understand the risks and benefits of participation before joining a trial. Clinical trial participants also have rights and protections.

What is the purpose of clinical trials?

Clinical trials can have different objectives that allow for differentiating between:

- Behavioural trials. They evaluate or compare ways to promote behavioural changes aimed at improving health.

- Diagnostic trials. They study or compare tests or procedures to diagnose a particular disease or condition.

- Prevention trials. They look for better ways to prevent a disease in people who have never had it or to prevent its recurrence. Approaches may include medication, vaccinations or lifestyle changes.

- Quality of life trials, or supportive care trials. They explore and measure ways to improve the comfort and quality of life for people with a condition or disease.

- Detection trials. They evaluate new ways of detecting diseases or health conditions.

- Treatment trials. They evaluate new treatments, new drug combinations or new approaches to surgery or radiotherapy.

Clinical trial phases

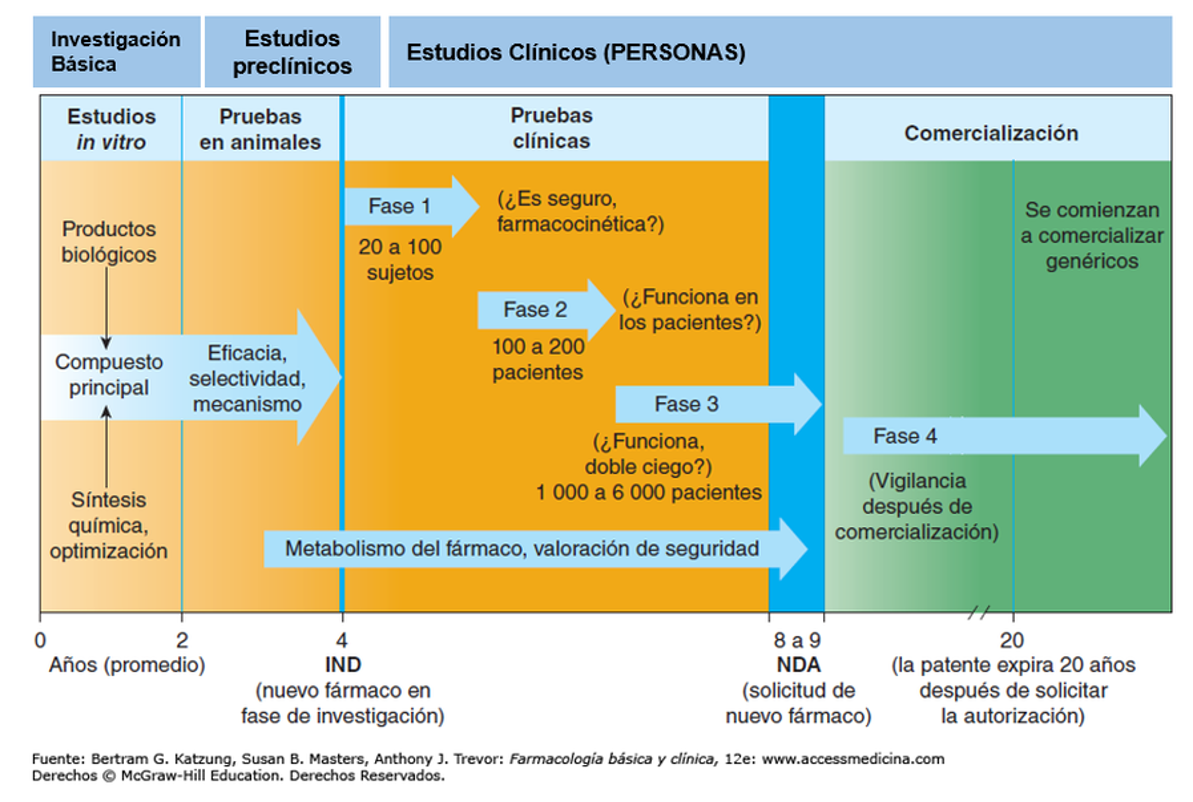

For a drug to come on the market and therefore be considered an effective medicine for a specific ailment(s), it needs to pass a series of ESSENTIAL and MANDATORY phases (both practical and legal) and tests

As can be seen in the graph, a medicine can have a testing, verification and monitoring phase of more than 10 years. In vitro studies test their efficacy in cells, then they are tested in animal models, followed by clinical trials in humans. Initially with a very small subgroup and later in larger groups. In turn, many Phase 3 clinical trials are conducted in a “double-blind” manner, meaning that the patient does not know whether he or she is taking the tested drug or a placebo, and neither does the doctor. All this in order to avoid any arbitrariness.

Each phase of a clinical trial has a different purpose and helps researchers answer different questions.

- Phase I trials:

The first group of people included are usually small (often up to a dozen), they receive a low dose of treatment and are closely monitored. If only minor side effects occur, the next small group of participants receives a higher dose. This process continues until doctors find the dose most likely to work, while maintaining an acceptable level of side effects.

The first group of people included are usually small (often up to a dozen), they receive a low dose of treatment and are closely monitored. If only minor side effects occur, the next small group of participants receives a higher dose. This process continues until doctors find the dose most likely to work, while maintaining an acceptable level of side effects.

At this stage, safety is the main priority. The research team is watching for any serious side effects. Due to the small number of people in Phase I trials, side effects that are rare may not be observed until after the inclusion of more participants. While some people may benefit from participating in the study, how well the disease responds to treatment is not the focus of phase 1. Although they carry a higher potential risk, as people with life-threatening diseases, and given the possibility of some benefit, patients sometimes opt to participate in Phase 1 when all other treatment options have already been tried without success.

- Phase II trials:

If a new treatment is found to be safe in Phase 1, then it proceeds to Phase 2 to determine its efficacy in certain types of pathologies, in particular cancers. The benefit that doctors are looking for is variable, it may involve evidence that the cancerous tumour has shrunk or disappeared, or it may involve the cancerous tumour not growing (or growing more slowly) for a longer period of time than expected. In some studies, the goal may be an improvement in quality of life. As a general rule, it is expected that receiving treatment will result in a longer (or better) life expectancy than would be expected without treatment.

If a new treatment is found to be safe in Phase 1, then it proceeds to Phase 2 to determine its efficacy in certain types of pathologies, in particular cancers. The benefit that doctors are looking for is variable, it may involve evidence that the cancerous tumour has shrunk or disappeared, or it may involve the cancerous tumour not growing (or growing more slowly) for a longer period of time than expected. In some studies, the goal may be an improvement in quality of life. As a general rule, it is expected that receiving treatment will result in a longer (or better) life expectancy than would be expected without treatment.

Phase II involves between 25 and 100 people with the same pathology receiving the new treatment. Treatment is administered according to the dose and method determined to be the safest and most effective in Phase I of the trial. Generally, in Phase II, everyone receives the same dose. However, in some phase II trials, people are randomly assigned to different treatment groups. In these groups, different doses may be given or the treatment may be administered in different ways, to see which offers the best balance between safety and efficacy. In Phase II clinical studies, the large number of patients treated makes it possible to deduce the number of side effects that commonly occur. If enough patients benefit from the treatment and the side effects were not very harmful, then the phase III clinical trial proceeds.

- Phase III trials:

Treatments that have been shown to work in phase II clinical trials usually have to successfully pass another phase before they are approved for widespread use. Phase III clinical trials compare the safety and efficacy of the new treatment with the standard treatment currently available. Because doctors do not yet know which treatment is best, study participants who are to receive the standard treatment and those who are to receive the new treatment are often chosen at random (randomisation). When possible, both the doctor and the patient are unaware of the treatment the patient is receiving. Such studies are known as double-blind studies. Most Phase III clinical studies include a large number of participants, at least several hundred. These studies are usually carried out simultaneously all over the country (and even around the world). These studies usually take longer than Phase I and II studies. Phase III may include placebos (substances that lack curative action, but look and taste like a real drug, but are never used alone if a treatment that works is available. Thus a person who has been randomly assigned to receive a placebo may also receive a conventional treatment. As with the other phases of clinical trials, patients are carefully screened for side effects and if they are too problematic to manage, the trial is discontinued.

Treatments that have been shown to work in phase II clinical trials usually have to successfully pass another phase before they are approved for widespread use. Phase III clinical trials compare the safety and efficacy of the new treatment with the standard treatment currently available. Because doctors do not yet know which treatment is best, study participants who are to receive the standard treatment and those who are to receive the new treatment are often chosen at random (randomisation). When possible, both the doctor and the patient are unaware of the treatment the patient is receiving. Such studies are known as double-blind studies. Most Phase III clinical studies include a large number of participants, at least several hundred. These studies are usually carried out simultaneously all over the country (and even around the world). These studies usually take longer than Phase I and II studies. Phase III may include placebos (substances that lack curative action, but look and taste like a real drug, but are never used alone if a treatment that works is available. Thus a person who has been randomly assigned to receive a placebo may also receive a conventional treatment. As with the other phases of clinical trials, patients are carefully screened for side effects and if they are too problematic to manage, the trial is discontinued.

- Phase IV trials:

When Phase III (and some even Phase II) clinical trials report that a new drug is more effective or safer than the current treatment, it is submitted to a regulatory agency (FDA in the US or EMA in Europe) for approval. Both of these review the results of the clinical studies and other relevant information. Based on the review, it is determined whether the treatment is suitable for use in patients with the disease for which the drug was tested. If approved, the treatment generally becomes the standard treatment, and subsequent new drugs may be compared against it before they are approved. If the agencies consider that more evidence is needed to prove that the benefits of the new treatment outweigh the risks, it may ask for more information, or even for further studies to be conducted. Drugs approved by the FDA or EMA are often kept under observation for a long time through phase IV studies. Even after a new medicine has been tested on thousands of people, the full effects of the treatment may not yet be known.

Approval by the FDA or EMA does not necessarily mean that a drug is available in all countries. There is a process, which is unfortunately very slow and complex, by which the health authorities in each country authorise their use, under which indications and at what reference price. In Spain this is granted by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products (Agencia Española del Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios).

The experience of a clinical trial

As a clinical trial participant, you may work with a health care team, and you may have to go to a hospital or other location. Everything that happens during the experience is based on a plan called a clinical trial protocol.

There are governing bodies, called Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), which approve protocols and are responsible for ensuring the safety of participants. The research team also acts in accordance with other national and international standards that protect participants and help produce reliable study results.

Before you join a clinical trial, you will be given all the information about the study, what procedures you will undergo, how much time you will need to spend on aspects of the study, and any other information you should know. Once your questions have been answered and you feel comfortable, you will be asked to give your consent to participate.

During a clinical trial, you may see doctors, nurses, social workers and other health care providers who will closely monitor your health. You may have to undergo more medical tests and examinations than you would have if you were not participating in a clinical trial. You may also be given other tasks, such as keeping a record of your health or filling in forms about how you are feeling.

If you decide that a trial is not for you, or you no longer wish to participate, it is important to remember that you can withdraw at any time. Your participation will not affect your regular medical care.

Links of interest on other topics related to clinical trials

- What are pseudotherapies? Reality and dangers. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in spanish)

- What is a clinical trial? SEOM (Spanish Society of Medical Oncology)

- Hemotrial. Clinical Trials Search Engine of the SEHH (Spanish Society of Haematology and Haemotherapy)

* In accordance with Law 34/2002 on Information Society Services and Electronic Commerce (LSSICE), the Josep Carreras Leukemia Foundation informs that all medical information available on www.fcarreras.org has been reviewed and accredited by Dr. Enric Carreras Pons, Member No. 9438, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and Senior Consultant of the Foundation; and by Dr. Rocío Parody Porras, Member No. 35205, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and attached to the Medical Directorate of the Registry of Bone Marrow Donors (REDMO) of the Foundation).

Become a member of the cure for leukaemia!