A recent study led by Dr. Manel Esteller, Director of the Josep Carreras Institute, shows how DNA methylation profiling in a common type of blood cancer, myelodysplastic syndrome, predicts whether the patient will respond to treatment. This type of cancer can progress to acute myeloblastic leukaemia, a much more serious disease. The outcomes could help in the early detection of patients who are resistant to demethylating drugs and in the design or administration of alternative treatments.

There are many anti-cancer genes that are no longer active in human tumours, preventing them from carrying out their protective function against cell transformation. One of the main mechanisms used by cancer cells to silence these ‘good’ genes is the addition of a chemical modification called methylation, which results in the loss of gene expression. As this is a simple addition of a single “methyl” group, drugs have been designed to erase this signal and they have already been approved for use in cancer. These hypomethylating drugs are mainly used in malignant blood diseases such as leukaemia.

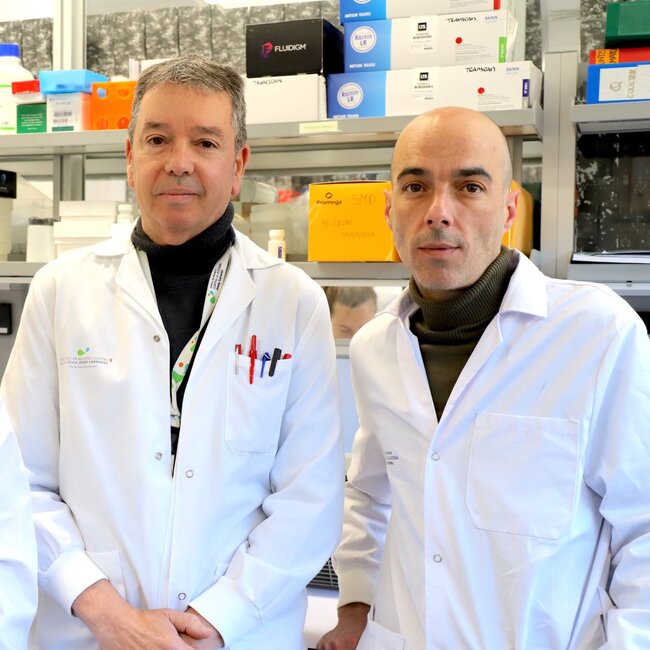

An article led by Dr. Manel Esteller, Director of the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute (IJC), ICREA Research Professor and Professor of Genetics at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Barcelona, published in the British Journal of Haematology, shows how the DNA methylation profiling in common leukaemia predicts whether the patient will respond to treatment.. The groups of Dres. Lurdes Zamora, Blanca Xicoy and Dr Francesc Solé from the Josep Carreras Institute, as well as researchers from the Vall d’Hebron Hospital and the University of Bologna, have also collaborated in the study.

«Our research has analysed nearly 1 million genome methylation signals in patients affected by a type of blood cancer called myelodysplastic syndrome and who have been treated with the demethylating drug. We have found an epigenetic ‘fingerprint’ that is associated with a good clinical response to these drugs, which can help in the early detection of patients who are resistant to demethylating drugs and in the design or administration of alternative treatments», comments Dr Esteller on the article published in the official journal of the British Society of Haematology.

Dr Esteller says they detected general patterns linked to the efficacy of the hypomethylating drug, but also single genes, which could facilitate the development of rapid and relatively inexpensive biomarkers to select responder patients and prepare rescue strategies for the rest. The researcher adds: «The genes we have found give us clues about the mechanisms involved in hypomethylating agents’ sensitivity. Some of them are tumour suppressor genes that now ‘wake up’ to inhibit tumour proliferation, as expected. In other cases, however, what the genes reactivation by the drug is likely to do is to produce proteins (antigens) and other molecules that alert our immune system to fight the disease. These data further support the use of cancer immunotherapy, which is likely to work even better in combination with the use of epigenetic drugs, such as the demethylating drugs included in our study».